.jpg)

There are some feats that are so staggering, so monumental that they tower above all other accomplishments in their field, inspiring awe and admiration from the contemporaries of those responsible. The 27-year-long, 6,000 page run of Cerebus the Aardvark is not one of those feats. If you go by pure numbers, Cerebus is hard to beat. It's the longest running comic narrative in history written and drawn by the same creative team. It has won every major comic award given in the industry. Perhaps most impressive is that its creator, writer and artist Dave Sim, performed the author's equivalent of Babe Ruth calling his shot: early in the run, he announced that Cerebus would run for exactly 300 issues and conclude in March 2004. Some people thought he was a genius, others thought he was crazy-- but sure enough, issue 300 rolled off the presses on March 2004, and Cerebus faded into comic book history.

"Why don't I already know about all this?" you may be thinking. "If Cerebus is such an incredible achievement in the art of comic book storytelling, why isn't it more of a household name? Where's the Cerebus movie? The Cerebus action figures?" The first answer is as mundane as the reality of circulation numbers. At its height, Sim's studio Aardvark-Manaheim printed 30,000 copies of Cerebus per month, at a time when titles like Superman and Batman sold in the hundreds of thousands. By the time it concluded, Cerebus shipped far fewer copies than it did at its pinnacle. Such is the fate of an independent publisher: you trade wealth and repute for the freedom to make every creative decision on your own. Exceptions, such as Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird's Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, can probably be counted on one hand.

.jpg)

More consequential in securing Cerebus's obscurity, however, is the simple fact that Dave Sim arguably went crazy during the course of writing it. Particularly during the last third of the series, but foreshadowed in not-so-subtle fashion in prior issues, Sim slowly began to work his off-the-hinge social and religious views into Cerebus until it became little more than a mouthpiece for his warped politics. As a result, what was once an epic adventure full of drama and mythological intrigue degenerated into an incoherent mess of a narrative, with only a few sparks of genius still surfacing every so often.

.jpg)

Therefore, rather than being regarded as a towering accomplishment of its medium, Cerebus is something akin to TV's Seinfeld. That sitcom had such an awful series finale (not to mention an overall lousy final season) that it cast a pallor over the many hilarious seasons that preceded it. People cringed at the mention of Seinfeld for years, only recently warming back up to it through reruns of the much funnier early years. Likewise, it seems that only a minority remember Cerebus's first 200 issues or so for the grandiose stories they were, despite such a drastic decline in the final years. Perhaps the greatest factor keeping Cerebus from being remembered with fondness and respect is Dave Sim himself, who severed ties with most of the comics community, and even his family, to live an ascetic lifestyle within the confines of his odd system of beliefs. He no longer seeks the adoration of the masses, and the masses are disinclined to award it.

CAUTION: THERE WILL BE MAJOR CEREBUS SPOILERS BEYOND THIS POINT. THERE WILL ALSO BE SOME EXPLORATION OF DAVE SIM'S PHILOSOPHICAL VIEWPOINTS, CONSIDERED TO BE HIGHLY OFFENSIVE BY MANY.

Cerebus began as a simple parody of the sword-and-sorcery genre, lampooning Conan the Barbarian, Red Sonja and even more mainstream superhero comics. Most issues were self-contained stories. To read the first dozen or so issues you wouldn't expect Cerebus to expand into a sprawling universe with detail rivaling that of Star Wars or Dragonball. At some point in those early issues, Sim began to see his titular anthropomorphic aardvark as a vehicle for something much larger than he originally set out to do. Issue 20 was the first, narratively and artistically, to be an experimental departure from traditional storytelling. Cerebus spends the entire issue in his unconscious mind, arguing between different fictional political parties.

Soon thereafter, Sim ditched the stand-alone stories entirely and began the series' first massive story arc, "High Society." Over the next 25 issues (or more than two years), Sim chronicled Cerebus's rise to power as the Prime Minister of the city-state of Iest, and all of the political intrigue and manipulation that bubbled beneath the surface on the way. Noticeably, Cerebus ceased to be an action/adventure story altogether-- the aardvark barely swung his sword through the entire tale. Rather than alienating readers with its abrupt shift in tone, "High Society" elevated Cerebus out of obscurity to become a widely respected independent comic, lauded for its layered characters and satirical themes.

The next arc, double the size of "High Society," continued the political intrigue while introducing a new satirical element aimed at organized religion. "Church & State" actually sees Cerebus become the pope of the Western Church (ideologically in conflict, of course, with the Eastern Church). If it wasn't apparent already, it becomes clear in "Church & State" that Cerebus is not meant to be a likable character in the traditional sense. He can be downright evil, in fact-- early in the story he punts a baby and an old man off the roof of a building to demonstrate his papal power, then demands that the destitute citizens of Iest give him all of their gold in order to prevent the end of the world. He may be a little bastard, but his malicious antics regularly bring the laughs.

In both "High Society" and "Church & State," Sim shows a knack for bringing back formerly inconsequential characters from the more carefree early issues to play new roles in the epic storylines that follow. The most prominent example is Jaka, who debuted as a tavern dancer in what was likely intended to be a one-shot appearance. Typifying the radically changed tone of the series, Sim brings Jaka back into Cerebus's life, now as a character with real pathos. In "High Society" he sows the seeds of an ill-fated romance between Jaka and Cerebus (who is almost always treated as if he were as human as any other character). Unfortunately, the later issues of Cerebus, after Sim went "over the edge," bring a bitter conclusion to the story, due largely to his increasing disdain for women.

.jpg)

At the conclusion of "Church and State," Cerebus has an "ascension," a term used in the series for a unique religious experience. He travels to the moon and meets "the judge," who oversees humanity and tells Cerebus of the nature of the god Tarim in one of the most outlandish, metaphysical scenes in the series. The judge also predicts that Cerebus will die "unmourned and unloved," setting the stage for the series' dark and twisted finale. When he returns, Cerebus finds that the ascension decimated much of Iest. He has lost the papacy and the city-state has been conquered by a brutal matriarchal regime from the East known as the Cirinists.

Thus begins "Jaka's Story," considered by many to be the pinnacle of Cerebus. Under the looming threat of the Cirinists, a disoriented Cerebus becomes the house guest of Jaka and her husband Rick, despite the fact that Cerebus is still deeply in love with Jaka. Concurrently, Sim interweaves a prose story about Jaka's childhood, a surreal tale told in the vein of the "unreliable narrator." The 23-part arc is sometimes pensive, sometimes quiet, until its concluding installments descend chillingly into the realm of the tragic. "Jaka's Story" features only five major characters, yet still captivates the reader better than anything that had come so far (and, many feel, would come after). It is the best showcase of Sim's storytelling ability in the visual medium of comics. In a fair world, Cerebus would be remembered for these chapters and not for the gobbledygook that would grow to be the norm after #200.

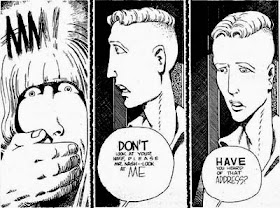

Personally, I was most affected by #136, in which Jaka and Rick, both having been arrested by the Cirinists because of Jaka's profession as a dancer, face interrogation by an amusing-yet-creepy Margaret Thatcher look-alike. To Jaka's horror, the Cirinists reveal to Rick that Jaka had induced an abortion of her unborn son out of fears that they would be unable to support a baby, and that she would no longer be able to earn a living as a dancer after childbirth affected her appearance. Enraged, Rick strikes Jaka and their marriage is torn asunder, all seemingly so that the Cirinists can "prove a point" to the couple about behavior they deem unscrupulous. Sim's art and words are truly haunting in these moments.

The next arc, "Melmoth," is an odd departure for the series, barely featuring Cerebus at all and focusing instead on a fictionalized version of Oscar Wilde in the final days of his life. Sim begins to increasingly incorporate straight prose into the comic format as Wilde's companion Reggie chronicles his deterioration in a series of letters to a friend. Sim would later repeat this formula, to less success, with fictionalized versions of Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

The final chapter of "Melmoth" is a segue into the massive "Mothers & Daughters" story arc that would carry Cerebus all the way to issue 200. Cerebus, having sat at a diner in a catatonic state since the arrest of Jaka and Rick, explodes with fury when he hears a Cirinist describe her treatment of Jaka while she awaited interrogation. For the first time in years, Cerebus finally picks up his sword, and thus begins a killing spree of Cirinists that carves a bloody path all the way to the leader Cirin herself. The opening chapters of "Mothers & Daughters" represent an incredible catharsis after witnessing the oppression of the Cirinists for more than 40 issues.

In perhaps the most pivotal moments of the series, Cerebus's murderous rampage leads to a four-way confrontation between Cerebus, his former adviser Astoria from his days as Prime Minister, and Cirin and Suenteus Po, the only two other aardvarks in existence. Po, who has somehow acquired an understanding of the aardvarks' mystical natures, explains to Cerebus and Cirin how their actions affect those around them in an unnatural way, and why he has chosen a path of pacifism. When Astoria and Po take their leave, Cerebus and Cirin square off in a brutal, bloody battle that lasts for ten issues, leading to another "ascension" for both.

Here's where Cerebus takes a dive into the truly controversial. "Mothers & Daughters" spans 50 issues, and is divided into four parts-- "Flight," "Women," "Reads" and "Minds." In "Reads," Sim interlaces the battle between Cerebus and Cirin with the prose writings of three characters-- Victor Reid, Rotsieve, and Viktor Davis-- who all serve as thinly veiled pseudonyms for Dave Sim himself. Beginning in #175, the characters' essays become increasingly misogynistic, perhaps with the intention of creating a parallel with the woman-ruled world of the Cirinists. The essays reach an apex in #186, wherein Sim outlines the philosophy that not only dominates the remaining 114 issues, but alienated thousands of fans and began the series' downward slide from lauded masterpiece to ill-perceived oddity.

In #186, Sim (writing as Viktor Davis) describes the male and female genders, and the universe as a whole, as the "Male Light" and the "Female Void." The Male Light represents creativity, ingenuity and reason that has guided and progressed us since the beginning of the human race. The Female Void is a construct of raw emotion and irrationality that eats away at the Male Light, constantly consuming it through a variety of means such as the institution of marriage, which he refers to by the term "Merged Permanence." He claims as unnatural the concept that people should pair up permanently with one another, and that the Female Void with its constant need for emotional connection is responsible for this. As a result of the temptations of the destructive Female Void, otherwise brilliant men with great things to contribute to society are seduced and subdued, manipulated into prioritizing marriage and family above all else.

That's just the tip of the iceberg, but more than enough to make apparent why a series with only hints of an anti-woman subtext suddenly exploded with controversy. As is often the case, the offensiveness of Sim's writing sparked a surge in sales of both individual copes of #186 and the "Reads" graphic novel. It would be hard to imagine anyone with a remotely balanced mentality not finding Sim's views of women to be abhorrent. The shame in this is that it muddies all the incredible work Sim had done to that point, including writing such a complex and fully realized female character in "Jaka's Story."

Much speculation persists amongst comic readers as to "what happened" to Dave Sim to make him develop such an out-and-out loathing for the female gender. Sim insists that there was no such incident that turned his heels on all of womankind, but instead that he came to his conclusions long ago and that #186 was "the point" Cerebus had been building toward. There are letter columns not printed in the book collections of Cerebus that could perhaps shed some light on the issue, but to me it's immaterial to the story of Cerebus the aardvark. Sim's unhinged viewpoints only become truly problematic when he begins incorporating them into the story proper, beginning with the next arc, "Guys." It's the primary reason for the downfall of the once-great series.

Despite being blindsided by the Viktor Davis "reads," "Mothers & Daughters" concludes on a grandiose scale. Cerebus's ascension concludes on Pluto, where Sim breaks the fourth wall and speaks directly to Cerebus as his creation for several issues. Cerebus has to confront a lot of his personal demons (as I said before, he is not the most likable guy, and Sim finally addresses it here), coming to terms with his unrequited love for Jaka and his mystical nature as an aardvark. Finally, he asks Sim to return him to a small tavern, where the majority of the next two story arcs would take place.

In my opinion, if you skip the prose portions of "Reads" and stop reading the comic altogether at issue #200, you've got yourself a pretty amazing epic. Up to that point, despite Sim's encroaching dementia, you still have a collection of both funny and touching stories and phenomenally rendered artwork by Sim and background artist Gerhard. However, with "Guys" and the following "Rick's Story," Cerebus takes a long, gray, pig-snouted nosedive. Both stories are loosely assembled ramblings by a collection of men in a bar, in which Cerebus eventually becomes bartender, extolling the evils of womankind and bemoaning their fates as drunks in the underbelly of the Cirinist society. When Jaka's ex-husband Rick returns and frequents the bar, we get an earful of his and Cerebus's philosophies about women and he even begins to form a delusional worship of Cerebus himself. This self-indulgence on Sim's part brings anything resembling a "story" to a grinding halt. The only other real content is a lascivious competition between Rick and Cerebus for a shallow sexual relationship with a buxom local stereotype named Joanne.

It's bad enough that Sim subtly changes Cerebus's character to reflect Sim's own more open misogyny, but even the once-great art suffers-- probably from repetition, as the majority of some 31 issues takes place in a BAR. Prose sections, now taking the form of religious scriptures, become more intrusive and taxing to read. The dialogue balloons are exaggerated to the extreme, with wide variation in font size and style to symbolize the nearly indecipherable accents with which the characters speak. Sim seems to have lost his understanding of the fine line between "clever" and "damned annoying" from the perspective of his readership, which had been dwindling since #186 and was dwindling still in these laborious arcs.

The series picks up a bit in "Going Home" and "Form & Void," in which Jaka reenters Cerebus's life, and they decide to return to his hometown. The interlude with Sim's fictionalized Ernest and Mary Hemingway is not as well conceived as the earlier "Melmoth," and I personally don't know about Hemingway to say if the story reflects any reality. Much of "Going Home" is introspective and a nice uptick in quality from the last two arcs. Unfortunately, Sim's special brand of lunacy intrudes again, and he re-frames Jaka as a spoiled stereotype, a shadow of the character she once was. Her relationship with Cerebus comes to an abrupt end when Cerebus returns to find his parents have died, and he somehow finds a way to blame Jaka for his misery. She then disappears from the story almost completely, bringing an abrupt and regrettable end to a once-rich character dynamic.

One subtle touch that Sim presents in the final story arcs is Cerebus's aging process. From "Rick's Story" through the second to last arc, "Latter Days," Cerebus slowly but steadily becomes more frumpy and fat, with a few wrinkles forming here and there. "Latter Days" takes place after a major gap in the timeline, during which Rick's writings have formed a religion with Cerebus as its head. Sim used many caricatures throughout Cerebus's 300 issues, but none were as dead-on as those of the Three Stooges, who kidnap Cerebus to force him to reveal his words of wisdom. After three years as the Stooges' prisoner, Cerebus finally generates a plan to overthrow the Cirinists. To his own surprise, the Stooges actually lead an army of men to victory.

Perhaps "Latter Days" would be funnier if the reader was not aware of the genuine anti-woman venom that inspires its narrative; however, its saving grace is that, unlike earlier arcs, it paints the men as bumbling idiots to such an extent that they look as bad as the women. I got a laugh out of the "complete dick" rule instituted after Cerebus's takeover, wherein any 12 men can declare one man a "complete dick" and blow his head off. Also, after the fall of Cirinists, the intellectually challenged mob of men take a vote on every woman in their hometowns, deciding which ones are "angels" (the hot ones) and executing the rest of them. I can't help but feel that Sim is now lampooning shallow men as much as he is shallow women.

I'll admit up front that I didn't even finish the later portion of "Latter Days," titled "Chasing YHWH." It's an almost entirely prose analysis of the Torah, by Cerebus and a caricature of Woody Allen, and it's every bit as tedious as that sounds. By this point in his personal life, Sim, who was once an atheist, had discovered faith and created his own amalgamation of the Abrahamic religions. Once again, self-indulgence intrudes on the concept of "story" in "Chasing YHWH," and Sim finds more excuses to blame women for all the evils of the modern world.

Appropriately, the finale of Cerebus is titled "The Last Day." While I was mesmerized by the horrific end Sim chooses for his protagonist, it betrays every notion of the bond an audience should develop with a character. In the final 100 issues, the character of Cerebus slowly transforms into little more than a vessel for Sim to offer his perspectives on topics that interest him. By the time we reach "The Last Day," Cerebus is a wrinkled old man vaguely resembling a Shar Pei, and there's no more appropriate visualization for Sim at this point-- a bitter relic condemning everything around him.

Cerebus spends the better part of "The Last Day" arguing with his caretaker to let him see his son-- born out of frame during the thirty year gap between story arcs-- before he dies. When he finally gets to see Sheshep, the long-lost son reveals that he has been converted to a new Cirinist movement, which has descended to the depths of pedophilia and grotesque genetic manipulation (in interviews, Sim has expressed his belief that this is the direction of Western culture). Cerebus attempts to kill his own son for his horrific deeds, but falls, breaks his spine, and is pulled into the afterlife, screaming for God to help him.

One can't help but be affected by the sheer darkness of Cerebus's conclusion, but to me there's no lasting value in it, as a work of fiction or as a supposed cautionary tale for our times. "The Last Day" and the later arcs in general are such a betrayal of the series' earlier greatness that any supposed wisdom Sim is trying to impart is lost on an audience mystified that an epic so great could go so far astray. Perhaps it all boils down to that ill-advised declaration that Cerebus would last for exactly 300 issues. A lot happens to a person in 27 years. In Sim's case, he went from an ambitious, talented independent comic creator to a recluse convinced that women and homosexuals were out to get him, and that God plans on sending about 99.9% of us straight to hell for sins such as child support and women's suffrage. Every ounce of that downward slide is reflected in his comic.

.jpg)

I have to backpedal a bit, lest I end on an unintentionally dour note. Despite its later decline, the bulk of Cerebus's story arcs are works of real genius. "High Society," "Church & State I and II," "Jaka's Story" and "Mothers & Daughters" in particular stand out as masterworks on par with great graphic novels like The Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen and Maus. Dave Sim is certainly not the first author whose personal life or later works made it more difficult to appreciate a career at its peak. Consummate readers know that those who dismiss a writer's entire catalog based on its lowest points will miss out on some good stuff, and Sim doesn't deserve that fate.

.jpg)

I heartily recommend the four story arcs mentioned above, each available in paperback, for the comics enthusiast or anyone looking to read something truly unique ("Mothers & Daughters" is divided into four books-- "Flight," "Women," "Reads" and "Minds"). "Melmoth" is another solid read, particularly for those of a more literary persuasion. Cerebus post-#200 is only for those who are truly daring, truly patient and nearly impossible to offend. With this particular aardvark, you have to pick your poison carefully.

No comments:

Post a Comment